Today is the anniversary of the famous "I have a dream" speech by Dr Martin Luther King.

In celebration of a man with drive to make change for not only himself, but for others, I'd like to pay special tribute to him today.

There are many reasons why I admire Dr. King, but as you can imagine the first and foremost reason is that he recognized social conditioning. In his case, it was the conditioning of a black race conditioned to think of themselves as something "less than" the whites. That conditioning has been spoken of on this blog often. We are conditioned socially, politically, by race, by nation, by religion, by society, by gender and even by our families.

Man in the Mirror PROJECT recognizes that when conditioning occurs we are not able to grasp who we truly are. We are not our color, our religiion, our gender, our country, or our families. We each have within us an individual light that when we shine it, like Dr Martin Luther King, we can make profound changes in our life and lives of people around us. May today remember that. May we remember people like Dr Martin Luther King and what he decided to do with his life. To stand up for change and to stand up for people and the equal rights that all should have because we are all human, we are all people, and we all live in the same world created by the same force.

'The moment we'd all been waiting for': March attendees remember King's historic 'dream' speech

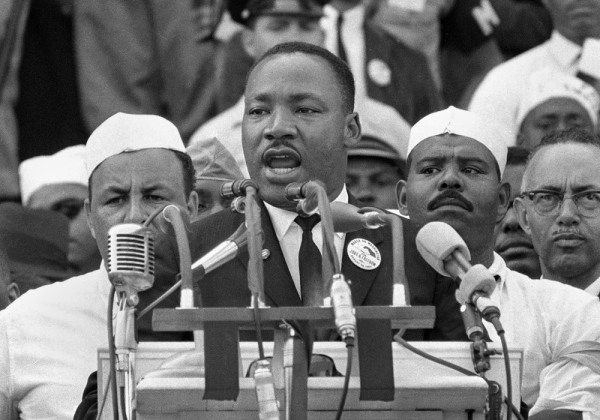

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, addresses marchers during his "I Have a Dream" speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington on Aug. 28, 1963.

Fifty years ago, more than 200,000 people gathered on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. NBC News asked six African-Americans who attended the march to share their memories of that day and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s "I Have a Dream" speech – and how they’ve passed on King's message to the next generation.

Jack White, 67, Journalist

Richmond, Virginia

In August of 1963, I was just out of high school and had a lot of curiosity about the civil rights movement. I grew up in Washington, a segregated city, and until 1954, I’d attended segregated schools.

On the day of the March on Washington, I put on a sport coat and a tie; it was sweltering hot. People were just more formal then. The powers that be were afraid of violence – can’t have all those Negroes there without trouble! – but it was the opposite. People were peaceful, respectful. Joyous and reverent would describe the mood. When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his famous speech it was all echoes to me. Still, I knew it was a historic moment because I could feel it in the crowd – this was the moment we’d all been waiting for.

Looking back, the point that resonates with me most is when he talked about the Declaration of Independence being a promissory note that all Americans should be treated equal, but America had given a check to citizens of color saying “insufficient funds.”That’s what bedevils us today, the contradiction between the magnificent visions that Dr. King outlined and the reality that we have still yet to deliver on that promissory note. How are we going to make America America for everybody who lives in it? That was always the issue.

I started having conversations with my kids about the notion of battling for justice as soon as I thought they were old enough to understand that whatever opportunities they enjoy come about as a consequence of what people did before them. On one hand, my children and grandchildren have opportunities somebody my age could never conceive. There’s nothing they can’t do. On the other hand, what they don’t have, that people my age had, is this sense of a historic moment when everything is changing.

Anne Ruth Borders-Patterson, 73, Civil rights activist and retired professor

Atlanta, Georgia

As a little girl in Atlanta, I went to segregated schools. We got all our books and desks second-hand from the white schools. I thought, why do we have to have books like this, all torn and tattered? There were all these rules that were supposed to make us think we were second-class citizens, though I never believed that.

In 1960, when I was a junior at Spelman College, I was one of the organizers of the Atlanta student movement. When we sat in at numerous “whites-only” restaurants, I was one of those who went to jail. Three years later, I drove to the March on Washington from Boston University, where I’d attended graduate school.

I never imagined a crowd like that. It looked magical, unbelievable. I remember not being able to move in the crowd. I remember children on their parents’ shoulders. And the number of white people out there -- to see all of them amongst the crowd of black people was amazing. When King talked about looking forward to his little children being able to grow up in a society where race was no longer defining who they were or who they would become, that stood out to me a lot. I could begin to dream as he dreamed.

Lurline Jones, 68, Basketball coach and educator

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

My mother had told me not to go to the march because she was scared of violence, but I just had to go. At the time, I was part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Morgan State College in Baltimore and had been on freedom rides to Cambridge, Maryland. I'd also participated in a sit-in with other students at a segregated movie theater in Baltimore. Some of us ended up arrested. I spent five days in jail. Afterwards, they integrated the theater.

The day of the march, the streets of Washington were filled with people coming from every direction, and everybody was going to the same place. We were arm in arm, singing, “We shall overcome.”

The line from Dr. King’s speech that really resounded with us, what we could hear loud and clear, was “free at last, free at last, thank God almighty, we are free at last.” The whole place erupted in cheers, people were jumping up and down, hugging and kissing.

I knew that I was doing something to let the people in this country know that you can’t continue to treat us the way you’ve been treating us, because we are Americans. We believe in the preamble and the Constitution. We fight in wars. We should be treated right. I felt very strongly that that’s what would happen. I really believed the dream.

I was with my grandchildren the other day, and I was telling them about the march. I wanted them to know about it, and about Dr. King. I told my son, “Please make sure that my grandchildren will always remember that their grandmother was there, and that their grandmother has always been a fighter and continues to be a fighter for equality.”

All the things that we marched for in 1963 are basically the same problems we face in 2013. In some instances, doors have opened, some doors have been shut, and some doors have been left ajar, but it’s still a process. I don’t think we are all the way there.

Jim Seida / NBC News

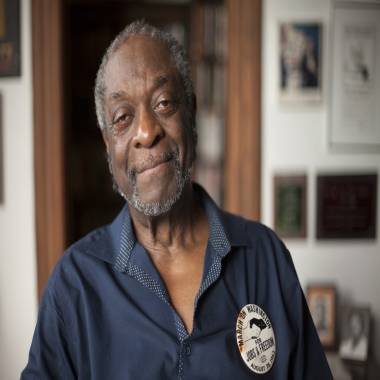

Les Payne, seen here at his home in Harlem, wears a button from the 1963 March on Washington, which he attended. For years before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday was observed as a national holiday, Payne and his wife would keep their children home on that day and teach them about the civil rights leader and his legacy.

Les Payne, 72, Journalist

New York, New York

On the day of the march, I took a bus to Washington from Hartford, Conn., where I had just graduated from the University of Connecticut. I was leaving for the army a few days later.

I didn’t go down there knowing Dr. King would speak; but I understood the significance of the march, although I was just coming into my political maturity.

At that point, politically I was struggling with overcoming a conditioned sense of inferiority, and I was trying to come to grips with that between both King and Malcolm X. I embraced them both; in fact, my own enlightenment was coming to realize that you didn’t have to choose between them.

When our kids entered first grade [we] started keeping them out of school on King’s birthday, long before it was a holiday. We would drive them to New York City for a program at one of the black churches, or we would listen to an album of King’s speeches and talk to them about who he was and what racism was about. I think King got his work done. The first Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act show his work, but until we (African-Americans) get rid of present vestiges of inferiority, we won’t be liberated.

George Mitchell, 69, Illinois NAACP State Conference President

Evanston, Illinois

In 1963, I was a Howard University student in Chicago for the summer. There were two trains that took people to the march. It’s a 12-hour ride or more.We sang songs, like “We Shall Overcome,” pretty much the whole ride; it gave you a sense that you were part of something bigger than yourself, and that no matter what happened, you were going to be ok. King’s speech was truly a dream speech; he talked about what it should be like in this country. It made me more aware of the injustices prevalent in American society and brought home the idea that people don’t just give you justice, you gotta demand it.

My wife and I used to tell our children, you have to be 10 percent better to be seen as equal. My children were always taught to respect themselves, respect others, but when people wrong you, stand up for yourself.

Keith Srakocic / AP

Nolan Atkinson Jr., left, George B. Vashon's great grandson and a lawyer from Philadelphia, addresses the Pennsylvania Supreme Court during the ceremony where the court awarded a posthumous Certificate of Admission to practice law to the descendants of Vashon in Pittsburgh, on Oct. 20, 2010.

Nolan Atkinson, 70, Trial lawyer and chief diversity officer of Duane Morris, LLP

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

I was attending summer school at Boston University where I just finished my junior year. I was assistant eastern regional Vice President of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, and the fraternity determined that all national officers should attend the March on Washington.

It was an attentive crowd. The speeches made many people believe that ending segregation, raising the minimum wage and making political change were things that could be achieved.

When Dr. King began with “I have a dream today,” the words were so simple and so eloquent that you just listened. It took on an almost church-like feel as he spoke. I think people left that march feeling like, we’re going to get this done.

Throughout my life, I have always tried to be a leader for diversity and inclusion. I try and enable people of color to have full opportunity. This was something that was passed down to my children.

King was a leader and that is what we need today, more than anything – leadership from the next generation. People who are willing to stand up and talk about things that are right, needed, and necessary. Certainly there have been achievements since King’s speech and his dream, but the kind of nation that King wanted, and believed was possible, is still a dream, not a reality --that’s something we have to continue to work on.

source: nbcnews.com

No comments:

Post a Comment